- Home

- Terry Hale

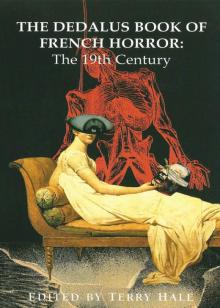

The Dedalus Book of French Horror: The 19th Century

The Dedalus Book of French Horror: The 19th Century Read online

THE EDITOR

Terry Hale has been an avid reader, collector and researcher of French nineteenth century horror fiction since reading Mario Praz’s The Romantic Agony as a student. From 1978 until 1989 he lived and taught in France, amassing a considerable amount of material on the French horror stories of the 1830s which later became the subject of his Ph.D. thesis at Liverpool University.

Between 1994 and 1997 he combined a career as a translator, editor and publisher of French fiction with the role of director of the British Centre for Literary Translation. He is now the British Academy Research Fellow at the Translation Performance Centre in the Drama Department of Hull University.

Terry Hale has edited for Dedalus Huysmans’ The Oblate of St Benedict and the Gaston Leroux novels The Mystery of the Yellow Room and The Perfume of the Lady in Black.

THE TRANSLATOR

Liz Heron was born in Glasgow and read Modern Languages at Glasgow University. She settled in London in 1976 and is a freelance writer and translator. She is the author of one non-fiction book, Changes of Heart (1986) and the editor of a collection of childhood autobiographies: Truth, Dare or Promise (1985). She edited Streets of Desire: Women’s Fiction of the Twentieth Century (1993).

Her many translations from French and Italian include for Dedalus the Rachilde novels Monsieur Venus (1992) and The Marquise de Sade (1994).

Contents

Title Page

The Editor

Introduction

Frédéric Soulié The Lamp of Saint Just

Eugène Sue The Travels of Claude Belissan

Alexandre Dumas Solange

Pétrus Borel Monsieur de l’Argentière, Public Prosecutor

Alphonse Royer The Covetous Clerk

Xavier Forneret One Eye Between Two

Marquis de Sade Dorci, or The Vagaries of Chance

Charles Baudelaire Mademoiselle Scalpel

Catulle Mendès The Penitent

Villiers de l’Isle-Adam The Astonishing Moutonnet Couple

Jean Richepin Constant Guignard

Charles Cros The Hanged Man

Jules Lermina Monsieur Mathias

Leon Bloy A Burnt Offering

J.K. Huysmans A Family Treat

Edmund Haraucourt The Prisoner of his Own Masterpiece

La Harpe Jacques Cazotte’s Prophecy

Charles Nodier The Story of Hélène Gillet$

Gérard de Nerval The Green Monster

Erckman-Chatrian The Invisible Eye

Henri Rivière The Reincarnation of Doctor Roger

Guy de Maupassant The Head of Hair

Théophile Gautier Mademoiselle Dafné

Jean Lorrain One Possessed

Sources/Translators

Copyright

INTRODUCTION

Anthologies of nineteenth-century French horror fiction – of which there have been two or three in recent years – tend to follow a well-beaten track. Théophile Gautier’s vampire story La Morte amoureuse of 1836 (translated variously as The Dead in Love and as Clarimonde) is almost sure to figure, as is Prosper Mérimée’s tale of an animated statue, The Venus of Ille, of the following year. From the fin-de-siècle, Guy de Maupassant’s tales of ‘psychic’ vampirism, The Horla (1886), and demonic possession, Who Knows (1890), are perennial favourites, as are two stories equally favourably disposed to the supernatural by Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, The Sign and Véra (collected by the author in 1883). A couple of other titles could be added to this list such as Gérard de Nerval’s magnificent tale of hallucination and madness, Aurélia (1855).

The present anthology has no intention of pursuing a similar course. Indeed, of the twenty-four stories collected here, some nineteen have never been published before in English (including tales by the Marquis de Sade, Théophile Gautier, Gérard de Nerval, and Villiers de l’Isle-Adam). Of the other five stories – namely, those by Alexandre Dumas, Erckmann- Chatrian, Charles Baudelaire, Guy de Maupassant, and J.-K. Huysmans – every attempt has been made to present material with which the reader may not be immediately familiar.

This is not to pursue a policy of novelty for the sake of novelty – it is simply intended to demonstrate the breadth and range of French writing in relation to the strange and macabre. Indeed, if horror fiction is a vehicle for exploring forbidden themes – a claim which will be put forward here – then it would not be untrue to claim that French writers in the nineteenth century proved themselves every bit as inventive as their British and American counterparts of the same period.

One should not, of course, necessarily expect them to explore precisely the same themes though. Indeed, it might be legitimate to enquire whether such perennial favourites – with their clear insistence on the supernatural – as Gautier’s The Dead in Love or Maupassant’s The Horla are as representative of French horror writing as we like to imagine they are. As dramatic and successful as these tales may be, they represent but one strand of horror fiction – that which came to be known in the 1830s as the conte fantastique – in nineteenth-century France. There are at least two other strands of equal if not greater significance which we ignore at our peril: the frénétique (or frenetic) story, with its strong melodramatic appeal, of the 1820s and 1830s (against which in a sense the conte fantastique was directly competing); and the conte cruel (what we might think of in English as grim little moral fables) which came to the fore half-a-century later (though the tradition is much older). As we shall see, neither of these two other strands are reliant on the supernatural to quite the same extent.

The first clearly recognisable development in the history of the nineteenth-century French horror story occurred in the early 1820s. Indeed, it was in 1821 that Charles Nodier coined the term ‘école frénétique’ – or ‘frenetic school’ – in order to designate the kind of writers who, in his words, ‘flaunt their atheism, madness and despair among the tombstones, exhume the dead in order to terrify the living, and torment the imagination with scenes of such horror that it is necessary to look to the terror-ridden dreams of the sick to find a model.’1

The sort of works he had in mind at the moment he wrote those words were mainly British: stories such as John Polidori’s The Vampyre of 1819, which was translated almost immediately into French (Nodier himself co-authored a successful French stage adaptation the following year) and novels such as Charles Maturin’s Melmoth the Wanderer of 1820 (of which two French translations appeared simultaneously in 1821). The enduring taste in France for reading material of this kind is clearly demonstrated by the fact that Nodier was reviewing a new French translation of a German horror novel about a murderous dwarf – Christian Spiess’s Das Petermännchen – which had first seen the light of day in 1791.

The French are not renowned for letting the grass grow under their feet though and, in the course of the two decades after the invention of the term frénétique, a great many authors tried their hand – with varying degrees of success – at writing novels and stories of the kind condemned (somewhat tongue-in-cheek) by Nodier. By and large, the more successful attempts soon owed but little, either in style or content, to their English or German counterparts.

Victor Hugo’s Han d’Islande (1823; tr. Han of Iceland, 1825), one of the best examples of the genre, is a complex tale of murder, betrayal and insurrection set in late medieval Iceland. Although the title refers to a mysterious dwarf (clearly modelled on that of Christian Spiess) of immense physical strength and capable of appearing at a moment’s notice, the most distinctive feature of the novel – and one which would clearly be of tremendous importance in the future development of the frénétique in France – was the author�

�s lugubrious humour.

This is nowhere better to be seen than in the chapter in which the cowardly Benignus Spaigudry, carrying in a sack the severed head of a drowned fisherman, takes refuge during a storm in the house of the Nychol Orugix, the public executioner. Much to the former’s discomfort, the conversation takes a predictable turn under the prompting of another stranded traveller:2

‘Master Nychol, what is the punishment for sacrilege?’ […]

‘That depends upon the nature of the sacrilege.’

‘If it should consist in the mutilation of the dead?’

The trembling Benignus expected at that moment the strange hermit would pronounce his name.

‘Formerly,’ answered Orugix, coldly, ‘they buried the criminal alive with the polluted body.’

‘And now?’

‘Now the punishment’s milder.’

‘Milder?’ said Spiagudry, scarcely breathing.

‘Yes,’ answered the executioner, with the satisfied air of an artist who knows his work. ‘First an S is branded with a hot iron on the fleshy part of his legs.’

‘And then?’ interrupted Spiagudry, painfully uttering the words.

‘Then they content themselves with hanging him.’

‘Mercy upon us!’ cried Spiagudry, ‘hang him.’

‘Why, what is the matter with you? You look at me as a criminal does the gibbet.’

‘I see with pleasure,’ said the hermit, ‘that people are now guided by principles of humanity.’

Following Hugo’s example, and quite unlike British or German horror writing from this period (which is largely incapable of self-irony), gallows’ humour of this kind would become one of the benchmarks of frénétique writing. Another excellent example is provided by Jules Janin in L’Ane mort et la femme guillotinée (1829; tr. The Dead Donkey and the Guillotined Woman, 1851). Indeed, Janin is said to have commenced the novel – which includes descriptions of a brutal animal fight, a macabre attempt to reanimate a body which has been submerged in the Seine for three days (an arm falls off), some form of horrendous treatment for syphilis which involves branding, and the guillotining of the heroine after she has murdered the man responsible for luring her into a life of prostitution (though not before she has been raped by her hideously deformed jailer) – as a spoof of the fashionable frénétique novel but finished by falling in love with his subject matter. If anything though the author was trumped by Honoré de Balzac (another writer, incidentally, whose literary career, like that of Victor Hugo, was closely associated at the outset with the frénétique) who, in a hilarious book-review, followed the dead heroine into the makeshift dissection-room of a group of medical students.3 But many equally striking examples of French gallows’ humour will be found in the stories in the opening section of this collection.

Behind the macabre laughter, these authors were exploring important issues though. During the course of the 1820s and early 1830s, there were many causes for anxiety – some of which are far from irrelevant even today. There was, for example, the controversial question of the death penalty, which Victor Hugo’s novel Le Dernier jour d’un condamné (1829; tr. The Last Day of a Condemned, 1840) deliberately set out to address. The rise in the student population led to questions being asked, not least by the students themselves, over the sacrilegious use to which corpses were put in the dissection theatres of the medical schools. There were more localised panics, such as that caused by the cholera epidemic of 1832.

More generally, there was the uncertain political climate – indeed, the entire period might be thought of as marked by fears of conspiracy, the threat of insurrection, and the various counter-measures taken by the authorities. The French Revolution of 1789 was by no means merely a distant historical memory (and, not surprisingly, many frénétique novels do deal directly with that period), it was also a defining event in people’s minds. When the relatively anodyne revolution of July 1830 broke out, there were those who feared a return to the Terror and those, such as the writer Pétrus Borel, who would have welcomed such a development. And, needless to say, in the world of popular literature, as elsewhere, all these various issues and events were quite capable of being kaleidoscoped together. Thus, the question of the abolition of the death penalty could easily shade into a consideration of the ethics of the French Revolution when, of course, the guillotine, intended initially as a humanitarian measure, was introduced. Indeed, if there is one defining image of horror writing throughout the nineteenth century in France it is that of the bloody head severed from the human trunk.

Three of the most prolific authors from the early 1830s onwards were Eugène Sue (1804–1857), Frédéric Soulié (1800–1847) and Alexandre Dumas (1802–1870). Of these, the first two started out primarily as frénétique writers while Dumas, now generally remembered as a historical novelist, began as a Romantic playwright. (The relationship between the frénétique and French Romanticism is by no means unproblematic – in many respects the former might be thought of the unacceptable face of the latter.) As the popularity of the frénétique began to wane in the late 1830s, all three directed their talents with considerable success to the new phenomenon of publishing novels, sometimes extremely lengthy ones, by instalment in the daily press.

The biographies of these writers tend to mirror many of the fears and anxieties of the time. Eugène Sue, who came from a family which had a long medical tradition, exemplifies this. His father, Dr Jean-Joseph Sue, had even conducted research during the French Revolution suggesting that the head – and not only the head but the arms, legs and inner organs of the body as well – continued to suffer pain for some time after the victim’s head and trunk have been separated by the guillotine. Nearly fifty years later, he would refer in passing to his father’s research in the pages of his best-known work: Les Mystères de Paris (1842–43; tr. The Mysteries of Paris).

Despite beginning his medical training – first under his father’s instruction, then during military service in Spain and, finally, as assistant surgeon in the French navy where he was sent to the Middle East and the West Indies – Sue immediately gave up the profession when his father died in 1830. Instead, he settled in Paris, in a state of some luxury, and devoted himself to writing. Over the course of the next eight years, Sue would make a major contribution to the development of the frénétique novel through his particular knowledge of mutinies, shipwrecks, sea warfare and the slave-trade. Indeed, it would not be wide of the mark to say that he was unrivalled in his description of maritime horrors. In Kernok le pirate (1831), for example, the captain of L’Epervier, having run short of cannon balls, blows his enemy to pieces by blasting them with a charge of silver coins; while El Gitano (also 1831) concludes with a pirate revenging the execution of his captain by infecting the whole of Cadiz with cholera by flooding the city with tainted cashmere shawls.

Any number of such episodes may be found in Sue’s principal works from this period: Atar-Gull (1831; tr. The Negro’s Revenge; or, Brulart the Black Pirate, 1841); La Salamandre (1832; tr. The Salamander, 1845); La Coucaratcha (1832–34), the author’s only collection of short stories; and Latréaumont (1837; tr. De Rohan; or; The Court Conspirator, 1845), a bloody historical novel whose title is said to have inspired the pseudonym of the author of Les Chants de Maldoror.

What may be less evident to readers more than a century-and-a-half later is that Sue’s tremendous cynicism and pessimism – particularly with regard to materialistic science, the myth of the noble savage, and the notion that all men are born equal – represents an ideologically motivated attack on the principal tenets of the Enlightenment, tenets which were later adopted by the adherents of the French Revolution. But it is for The Mysteries of Paris – a vast proto-detective novel largely set in the slums of Paris which took the whole of Europe by storm (six different English translations were at one time being published simultaneously) – that Eugène Sue is nowadays principally remembered.4 Apparently, it was during the writing of this immense work that he was converted, al

most overnight, to socialism (not all of his critics were convinced of his sincerity – indeed, Karl Marx was responsible for a scathing attack in 1844) such that his later writing implicitly serves as a refutation of his earlier works (though he never publicly disowned them).

In his day, Frédéric Soulié enjoyed the same level of popularity as Sue or Dumas. His first major prose work – and also his most frénétique – was a historical novel, called Les Deux Cadavres (1832), dealing with the English Civil War. The two corpses of the title are those of Charles I and Oliver Cromwell and the plot itself revolves round an obscure legend (known to Samuel Pepys and others but generally ignored by academic historians) that the latter issued secret instructions that he should be buried at Naseby. In Soulié’s novel matters are taken a step further and the bodies of the King and the Protector are switched – such that the Royalists, when they finally manage to locate what they believe to be Cromwell’s place of rest, desecrate the body of their own former master. It is this action, according to the author, which is responsible for causing the Plague of London.

Before his untimely death in 1847, Soulié went on to write more than two dozen plays and a similar number of novels – including a remarkable serial novel, entitled Les Mémoires du Diable (1837–38), which virtually invented the tradition of publishing fiction by instalments in the popular press. The story translated for the present anthology is taken from his first collection of short fiction, published in 1833.

The third musketeer of this opening section, Alexandre Dumas, is far too well-known to require more than the briefest of introductions here. So prolific was Dumas that by the early 1840s rumours had started to circulate that he bought up complete manuscripts from impoverished hacks toiling in garrets which he published under his own name. Although there was some truth to such stories, he was also an extremely versatile writer whose work was by no means limited to prose fiction: besides his dramatic contribution (in recent years both Kean and The Tower of Nesle have enjoyed successful revivals), he also wrote a considerable number of travel books (his adventurous life took him as far afield as the remoter provinces of the Russian Empire and the semi-barbarous kingdoms of North Africa). Perhaps it was this versatility which prevented Dumas from doing much more than occasionally toying with frénétique themes – though his 1849 collection of inter-locking short stories, Les Mille et un Fantômes (1849; tr. The Thousand and One Phantoms, 1849), clearly belongs to the genre. Appropriately enough, several of the stories deal with French revolutionary history – including the famous urban myth that Charlotte Corday, after being guillotined for the murder of Marat, blushed when the public executioner held up her decapitated head and slapped her face. (The same narrator, Monsieur Ledru, said to be the son of the physician to Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette, tells the story of Solange in this collection.)

The Dedalus Book of French Horror: The 19th Century

The Dedalus Book of French Horror: The 19th Century