- Home

- Terry Hale

The Dedalus Book of French Horror: The 19th Century Page 12

The Dedalus Book of French Horror: The 19th Century Read online

Page 12

‘It is upon its head.’

‘What about the diamonds?’

‘Upon its feet.’

‘Is it alive? Are you sure?’

‘Yes … yes … I can feel its breath on me.’

‘Farewell! Farewell! Poor little thing!’

‘Brother, let us be off!’

And, once back at their convent, the monks called upon God.

At daybreak, firm hands carried what had been entrusted to the monks intact to the chief magistrate of Tortosa; except that they told him they had heard crying and gone running to find the child between the ground and the skiff with one eye missing. The packet of papers contained a fortune for Blondina, without any clue to cast light upon the name of the donor. The chief magistrate cared for the child as if by Heaven’s command and when Blondina had grown up and he was dying, he told her: ‘Though you have no family, you are at least rich and free; young girl, do not abuse this! Let my memory be a help to you! Take this, keep it and read it often!’

The chief magistrate stretched out his arms, then died as he uttered the last of these words; and what came into Blondina’s near frozen hand was what one of the two monks had laid upon her head on that warm autumn night.

Here are the words of the monk.

†

By the holy cross that my finger has traced, and whose image must be precious to those whose souls are filled with God alone, little one, do not grow up before you die; this is the first wish in the depths of my secret thoughts; what would you do in the world? Living is damnation. Rise to heaven, graceful little one, while your thoughts are still unformed. Go and stand before God who loves children, who are as pure as is his name and is his majesty. Go! May he give you a place in his fine good heaven; go! may he rejoice at the sight of you; go! may he love you and bless you for ever and ever; go! Let it be allowed me, an old man who must stay on earth, of whom however there remains something of a heart that stirs, but more for God than for life, to tell you something of what I am feeling, you, pale and tender creature whom I call Blondina, because of those gold silken threads starting to play around your head to which I entrust these writings. Yes, I need to commend you to what exists, since they do not want you where you come from, you who were entrusted to me by one all powerful, who gave me an iron order to expose you in a skiff, with your fate cast to the wind and to men. No one forbade me to do this, no more than to place my withered lips on your smooth brow with the utmost holiness and purity in the world. I can also advise you, dear sweet child, that if love should touch you, or you should touch love, to take back to Heaven all the delights that your soul can feel. It is heaven that sends this love, my angel, but heaven wishes for its restitution, as alluring as it was before. Thence, true joy in all its purified plenitude; believe me, when you are at the age to read what I write, lovely little one whose gaze opens on mine as my eyes gaze on yours. Do not forgive yourself Evil, and tell yourself again and again that Good is like a piece of bread from which virtue must take nourishment at every hour of day and night. You have a fortune; but remember that you will not be rich with smiles unless your pockets are open to others; that you will not be warm in winter unless the poor have shod feet and clothed bodies, the poor wracked by blushes as well as by hardship, the poor whose doors you must open softly to throw them succour, and run from them fast. Amid everything that speaks you are what is called alone; poor little Blondina, but let my cross be your guide. Now, never love anything but God; motherless, poor little Blondina, without your mother! Kiss my cross, my child; do you see, the cross is the mother of those who are abandoned; kiss my cross; on one of the arms that it stretches out to you there is a tear, yes, a tear fallen for you, poor little Blondina, fallen for you!

*

Despite what the monk had wished for her, the little Spaniard had already lived twenty-seven years. But why did she let her hair hang over her face, blowing in great waves, and thicker on the one side than the other? It was because it was indeed true that Louminoso of Granada had replaced with a glass eye the one put out by a stick from the skiff blown into it. This endeavour and its success surpassed everything one might have imagined; the eye was finer, more transparent, more natural, more eye-like in other words. The colours were so artistically nuanced, the two sections of the cornea so delicately figured, the pupil so skilfully dilated, that one could almost make the eye move by staring hard at it with a dead man’s gaze, that is to say as fixed a one as possible; and since Louminoso, a man between two humps, believed he loved Blondina, who had made his heart speak, he had applied himself to this study for an enormous length of time, from what one could tell: ‘The unseeing eye seems to see better than the one that sees.’

Now let us return to the church where our two lovers are at prayer and at love. Although they were in substance their own masters, that is to say held in check by the laws of the country alone, they drew happiness from mystery, from silence, from shadow, from a gloomy light entering through dusty barred windows with a young hand that is aged and long-since buried. They liked these voices carried on the wind, no sooner there than dying away. Without quite knowing why, they delighted in seeing those long peculiar columns of atoms which dance in the sun, forever rejoining when broken and split by the child that runs across them, and they would tell themselves: ‘That is what we are, all the same; just a little more substantial, that is all.’

The chapel to which they directed their steps, after pouring out their souls before the tabernacle, and which served them as a holy drawing room, belonged to Blondina. It was small and arranged with flowers for God and Muguetto, who for some months now had picked his orange blossom there. Three times a week the Spanish couple had a rendez-vous there at the same time struck by the clock, as if only one who was masked could enter there, or with night darkness covering faces. This is why two doors were opened, one for the man, another for the woman. Doubtless you will be hard put to understand that one might seek for slavery in freedom; and yet is this anything other than that universal human wish: to want what one does not have, and no longer to want what one does have.

When, in this chapel they called Love-and-God-Chapel, Blondina and Muguetto were not conversing aloud from the heart, their words were murmured. Let us listen to them now.

‘Oh my Blondina!’ said Muguetto, ‘My true life, purity of my thought, do you well know that for me you are what the sun is for the world? The more we see it, the more we love it. You know well that when you walk I admire your very shadow, and I always fear that nothing on earth will remain of it? I stop, I look, I search; I am worse than a madman, am I not? This happens whenever I set out to follow you, leaving you ignorant that there is someone behind you walking in your footsteps. Most adored lover above all, yes, above all women, I have not enough soul for yours; it is true, listen, I swear it; and tell me, where do you come from? Can you not answer me, my poor child? Very well! No, do not torment yourself, you are turning pale, be calm, do not tremble unless it is from happiness. I shall say it for you: your father was a saint at the very least, and your mother a relative of the Virgin Mary. God must have commanded them to act as they did. So, forgive them; bless them as I do, do not be sad; I might not have you for myself if they were to make themselves known; let us bless them; will you? I am sure that you want to … There! I was certain that you did.’

Muguetto suddenly realised how loud his voice was in the chapel. All at once there was silence; the lovers prostrated themselves as if the good Lord had passed before them.

When they rose again, like a wild horse, the man from Tortosa pulled the Spanish woman to him, and afterwards, as if in a pool of ice, his face white as death and his lips purple-hued, he stammered, his gestures distraught: ‘Cherished soul, my Blondina! What I felt a moment ago with my brow against the marble is extraordinary. I was struck as if by a ghastly flash of lightning; I have a sense that you will not live for long. I heard a shuffling of chairs, a creaking of walls, a sigh, I know not what this was; but in it there was a

sound which sent me these words: SHE IS SOON TO BE DEAD.’

‘No doubt,’ the Spanish woman answered with a smile, ‘either heaven or hell will take me soon if you stop loving me, for there is no air I can breathe but that which your love gives to me.’

‘No! It is not that,’ the man from Tortosa replied, ‘it is something else. Later I shall tell you why I was weeping when I arrived. But I am still too frightened to do so now. It is strange! I am scarcely recovered … See how I tremble … Hold me for a moment … Here! Here …’

And in Blondina’s hand Muguetto’s lay hot with the sweat of mortal agony.

At that moment there was a peal of bells. Doubtless the two coffins that had just left the church were being put into their grave.

The man from Tortosa and the Spanish woman had left Blondina’s chapel and the town’s cathedral, and had gone to the house of Blondina, since Muguetto’s dwelling was distant. Here, as the agitation of his fright began to subside, he was able to smile again upon the purity of his thought, as he called his lover. She had made him be seated, then to lie down upon a fine day bed whose covering her own fingers had embroidered, and had sat at his feet regarding him, as ever, with delirious passion. It was only then that despair came upon her for the loss of half of her sight. Then she began to move about with frenzied agitation; and now her arms were jerking in spasm, and without a kiss from Muguetto who leapt up from the bed, they might well have remained so. But is not the mingled breath of a man and a woman who love one another the supreme balm that heaven gives to the earth?

‘Calm down,’ said Muguetto in tones almost as sweet as those he had presently heard and returned; ‘It is not good to let yourself be carried away like this. I don’t want this to happen any more, do you hear? I implore you a thousand times, naughty child that you are, since I find you well and I would not want you to be any different. Certainly not, that is not what I would want. Would you be little Blondina from the floating basket, grown into the passionate Spanish girl, dancing in a way that men would die for, with those feet as large as my finger? And it was at one of the salons of the duchess Florea that I noticed you, when the good magistrate took you there; for you go to salons, whenever you are so inclined. You are loved in Tortosa; of course your two horses are considered as a father and a mother, and your carriage like a family. How much men’s actions are made up of absurdities and injustices! But let us leave that aside; what does it matter? Are men my concern? Is there anything that lives in the world for me, except you? And should it happen again that you are discontented with what you are, and with your ignorance about your father and your mother, then I shall look at you no longer, I shall say to you no longer that I love you, you will go without kisses for two whole days. There! I feel restored now, I am better, I was burning in a fire; and you, my Blondina, oh yes, you will long be my Blondina. Who will make it otherwise? Heaven? Heaven is too good. Earth? Earth is not to be feared but by those who are afraid of it. Answer me, my lover, have you recovered from my fright? SHE IS SOON TO BE DEAD!’

‘What can I say, my Muguetto? You well know that in your presence the only language I have is my rapture. Does your voice not halt mine? All my heart has for yours is the madness of its beating; how would my lips speak that are burned by you? Nonetheless they still find the will to answer you that if a woman were to replace me by your side, I should wreak vengeance, for I should go mad. I believe not mad enough to be tied, to be confined; thus, now and then I could be there standing before you, at the very moment when you were least expecting it. I might be numb, my head drooping like the Redeemer on the cross, or else dancing like the first time I saw you; and with a diamond or two upon a rag that barely covers me, clutching you, wanting to play with you, mutely calling to you: Muguetto, you are faithful to me! See now, all of you who lie to me, that he is indeed faithful, for I am touching him, for I am holding him, for I am in his embrace! And my face would be horribly gaunt, and frightfully pale, and it would thrust itself upon your face and make it shudder.’

Muguetto thought for a moment, then replied: ‘If you were to deceive me, I should crack your skull to smithereens, and I should count the pieces and curse your soul anew for every one of them.’

‘My vengeance would be a better one than yours,’ Blondina answered serenely; ‘it would be the stronger because it would be slower.’

Shouts, bursts of laughter, sounds almost like screams echoed from outside, reaching the two lovers through a casement window.

‘Do you hear!’ the Spanish woman exclaimed, ‘That is Séraphine-the-lovesick-madwoman going by; she has not stopped yet! They say she loved someone. Muguetto, do you see those bones that are all she has for flesh on her face? I would have a face like hers. Do you see those lips flecked with white foam? I would have lips flecked with white foam. Do you see those arms, that unclothed neck? Mine would be the same. And that child she drags along with her, that someone left! Like her, I would laugh dementedly with grief, I would turn and look at people as she does, haggard and frightful, without telling them to leave me alone and keep their remarks to themselves; I would walk about like her mechanically and I would keep on walking so as always to have someone beside me. Do you see that big stone that someone just put in front of her and was knocked by her bare knees? Look! The skin has been torn away and we can see it is bloodied underneath. Well, my lover, I shall rise to my feet as she does, dazed and staining the cobblestones as the blood falls droplet by droplet. There! Now someone is throwing her a piece of bread; she is as agile as a monkey, she has not let it slip from her grasp! I too shall have bread and as she does I’ll devour it like an idiot. And do you see now, Muguetto, that handful of mud has hit her in the face! Mine too, oh yes, Muguetto, my face too will be lashed with mud if you stop loving me, and as I go by, before they lock me up, people will shout: Look, there is the sister or the cousin of Séraphine-the-lovesick-madwoman! Let’s have some fun with her; what do you say? Let’s have a bit of fun And after that I will only have the pity of the madhouse, and chains for my arms. What! We cannot see the-lovesick-madwoman any more; she has vanished; for now she has a mob upon her. Muguetto, there is more I have to say to you …’

‘No! Enough! Enough,’ the man from Tortosa broke in, shuddering.

‘Very well! Yes, it is enough; and now tell me why you were weeping.’

‘Because as I was on my way to the church I heard a man, his voice disguised, cast these hellish words upon my ears and those of every passer-by in Tortosa: “Handsome Muguetto with the orange flower, you are being deceived!”

‘It came from a window that I do not know; and the man’s head darted back in through the casement, like that of a snake into its coils.’

‘And you believed this voice?’ said Blondina.

‘If that had not been so, I should not have wept. There are beliefs that poison one so fast, that the poison burns or freezes tears. To think you were deceiving me! A free woman deceiving her lover! But imagine for a moment what this means: at least a thousand serpents with a thousand heads lying there around my heart, turning it into a grave; yes, a grave of writhing serpents in the sun where a living man would be cast. What would happen down there would not be more dreadful than what would happen to me, if I had believed what we have just spoken of. I would have been changed into a spectre by the time I reached the church, if my legs had kept me upright to get there. And then, as I entered and saw you, what phantom of grief would have struggled to reach you, striving to speak murmured reproaches! But, no avail! Every striving would have failed beneath despair’s abyss; and then, the vestiges of a human being would have fallen on the flagstones and would have turned to a mysterious dust.’

‘We are both insane,’ the woman of Tortosa said in answer; ‘Me over my folly of the lovesick madwoman, you over your vision in the church and your grave of serpents in the sun.’

‘That is very true,’ the Spaniard answered; ‘so I shall leave your hair which is moistened by my lips, and your hand which my own has c

aressed, and I shall place you in God’s keeping until first thing tomorrow; may he be with you always in your slumber, in your dreaming, in your blood! Tomorrow morning my Blondina, be ready at the day’s beginning; we shall go and love one another on the banks of the Ebro; we shall see the blue of the sky mirrored in its course, and hear the breeze and the sighing waves sing their seguidillas. Be ready. Farewell! My life for you, until my death on this earth!’ The man of Tortosa made off, and as he went he could hear his lover calling out: ‘Muguetto, my dear Muguetto, my adored one, more of your words, more! …’

Soon after her lover had left her, she received two visits, the first of which was like her mortal agony, the second her death.

This is what happened.

A servant came in to announce that a man in a long robe and with a long snow-white beard, was asking to see señora Blondina for a moment.

‘Show him in,’ she stammered, still a-flutter from Muguetto’s departure.

The white-bearded man appeared. The double door closed behind him. Then Blondina was face to face with a monk.

You have guessed it; it was indeed the one who had exposed the little girl to the elements in the skiff, and written what was found placed upon her brow.

Upon a sign from the señora, he explained himself as follows. His head shook with age like that of a plaster rabbit.

‘Child Blondina,’ he began, after looking around to make sure there were only the two of them, ‘you are startled to hear your name spoken thus without ceremony and to be so addressed; but the one who stands before you, child Blondina, as I call you again, is the monk Monako, known as the Very Aged; but it is something other than his one hundred and eight years which endows him with the right to speak in this way; it is memory and truth. Shall I tell you in few words what these are? I have come to do that; I promised; moreover, it had to be done; I could not do so before, for ever since your birth until this moment I have always been spied upon, as closely as is a knife to the throat that it cuts. You are settled again, are you not? What does this mean, what is this all about? You are wondering. Well I am here, do not lose patience. Do you hear how I stammer? Yet less these days; do you see how time has addled my head? It empties it faster every minute, and I must make haste to forestall it by drawing out what duty compels me to communicate to you. It is as well that I do so now; perhaps two days or two hours later would mean you knew nothing; God in heaven! what little did it matter, besides; what little did it matter. Am I mad? No, I am old, my child!’

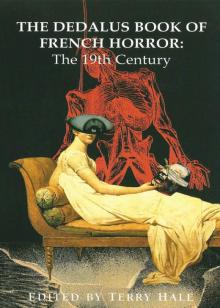

The Dedalus Book of French Horror: The 19th Century

The Dedalus Book of French Horror: The 19th Century