- Home

- Terry Hale

The Dedalus Book of French Horror: The 19th Century Page 16

The Dedalus Book of French Horror: The 19th Century Read online

Page 16

The Count arrived home and prepared for his departure. But a fatal premonition, the interior voice of nature which we ignore at our peril, resulted in him taking into his confidence one of his friends who was in his service; he admitted that he could not hide even from himself that some impenetrable emotion advised him not to become involved in this affair … But his kindness got the better of him, nothing could compare with the pleasure Dorci felt at doing good, and he set out for Rouen.

When he arrived there, the Count called on all the judges, informing them that he would act as guarantor for the unfortunate Christophe, should that be necessary, and that he was convinced of the man’s innocence, so much so that he would stake his own life, if required to do so, on that of the accused. He asked to see Christophe, permission was granted, and the Count was so pleased with the replies he received to his questions that he became more than ever convinced that the man was incapable of the crime of which he had been accused; Dorci then declared that he would openly assume the peasant’s defence and that if, by any mischance, the man was convicted, he would apply to the Court of Appeal and write a memoir on the case which would be distributed throughout France, bringing shame on any magistrate so unjust as to condemn a man so self-evidently innocent.

The Count de Dorci was well-known and highly-regarded in Rouen, his birth and rank opened people’s eyes; it was felt that the case against Christophe had been conceived a bit hastily; the investigation was re-opened, the Count paying all the attendant costs; amazingly, there was not the slightest piece of evidence to be found against the accused. It was at that moment that the Count de Dorci sent Annette’s brother home to his mother and sister with the instruction to set their minds at rest, assuring them that Christophe would soon be set free.

Everything was going extremely well when one day the Count received the following anonymous note:

‘Abandon the case you are following immediately. Stop at once all investigations into the death of the man in the forest. You are digging your own grave. Your virtues will finish by costing you dearly! Cruel man, how I pity you … But it is perhaps already too late. Farewell.’

A dreadful shiver ran through the Count as he read this and he nearly fainted; taken in conjunction with his earlier premonition, this fearful message proved to him that he was threatened by some sinister and inevitable force. He remained where he was, but he became totally inactive. By the Grace of God, the warning was a just one. But it was already too late, he had already made too much progress, the fatal steps he had taken had succeeded only too well.

At eight o’clock in the morning, exactly two weeks after his arrival in Rouen, a councillor in the city administration whom he knew, rushed in to see him:

‘You must go at once, my dear Count! You must leave this very instant!’ he exclaimed, breathlessly. ‘You are the most unfortunate of beings; may the memory of your unfortunate adventures never become known! It could only convince people of the dangers of virtue and so cause them to abandon such a cult altogether. If it were possible to believe in an evil providence, then today would surely be the day on which to do so!’

‘You terrify me, sir! What has happened, I beg you?’

‘Your protégé is innocent, he will be set free any moment, your investigations have led to the discovery of the murderer … Even as I speak to you, he is already under lock and key. What more information do you need?’

‘Speak, sir, speak! Drive the dagger into my heart … Who is it?’

‘Your brother!’

‘My God! Not him!’

And Dorci fell to the floor; it was more than two hours before he showed signs of life. When he came round, he was in the arms of the same friend who, fearing to lack impartiality, had not been included among the panel of judges and was able, when the Count opened his eyes, to tell him what followed.

The murdered man was the Marquis’s rival; they had been returning together from Aigle; during the course of the journey a dispute had broken out between them; the Marquis, furious that his enemy would not agree to fight a duel with him, and realising that he was not only cowardly but treacherous, had knocked him from his horse and trampled him to death. After this, the Marquis, seeing his adversary lifeless on the ground, had totally lost his head and, rather than running away, had contented himself with killing his horse and hiding it in a pond. Then, although he had told everybody that he was going away for a month, he had brazenly returned to the small town where his mistress lived. On seeing him, everyone had asked for news of his rival; but he replied that they had only travelled together for an hour or so and that they had then separated.

When news of his rival’s death and the story of the woodcutter accused of having killed him reached the town, the Marquis listened on without the least sign of agitation and even recounted what he had heard just like everyone else; but the Count’s secret enquiries produced more accurate information and suspicion fell squarely on the Marquis. It being impossible now to defend himself, the Marquis no longer tried to do so; capable of acting in the heat of the moment, he was entirely ill-equipped for crime and avowed everything to the officer who came to question him. Allowing himself to be arrested, he said that they could do whatever they liked with him. Unaware of his brother’s role in this affair, and believing him tranquilly installed at home in his château where he himself had hoped to be rejoining him any day now, the only favour he asked for was that his disgrace should be kept, if possible, from the brother who adored him and who would be precipitated into an early grave by this news! With regard to the money which had been stolen from the corpse, this no doubt was the work of some poacher or other who, for obvious reasons, had not come forward. The Marquis was then taken to Rouen, and it was at that moment that the Count was informed of what had happened.

Dorci, once he had slightly recovered from his initial despondency, did everything in his power, whether on his own account or through his friends, to save his wretched brother. Everyone sympathised with him, but their ears were closed. He was even refused the satisfaction of visiting him and, in a state difficult to describe, he left Rouen the day of the execution of the mortal who was not only the most precious and sacred person to him in the entire universe but whom he himself had been responsible for sending to the scaffold. He returned briefly to his country estate but with the intention of leaving it shortly for ever.

Annette knew only too well the identity of the victim who would be immolated in the place of the one to whom she owed her existence. She and her father courageously called at Dorci’s château; they both fell at the feet of their benefactor, banging their foreheads on the ground and demanding the Count to take their lives in exchange for the one he had sacrificed in their favour; if he would not do this, then they begged him at least to allow them to act as his unpaid servants for the rest of their existence.

The Count, as prudent in the midst of misfortunes as charitable in prosperity, but whose heart had become hardened by his excessive suffering, was no longer capable of responding to such extravagant sentiments and ordered the woodcutter and his daughter to leave, recommending that they made the most of the charitable action which had cost him his honour and his peace of mind. The wretched father and daughter dared make no reply and disappeared.

The Count gave all his property to his closest relatives, retaining only an allowance of a thousand écus for his personal use, and spent the remaining fifteen years of his melancholy existence, which were marked by continual acts of despair and misanthropy, in a retreat far from public view.

Mademoiselle Scalpel

Charles Baudelaire

As I approached the furthest edge of the suburbs, under the gas lamps, I felt an arm gently insinuate itself next to mine and heard a voice whisper in my ear:

‘Aren’t you a doctor, sir?’

I scrutinised my unknown companion – a tall, well-built woman with wide eyes, discreet make-up, her hair floating in the breeze with the ribbons of her bonnet.

‘No, I am not a

doctor. Leave me alone.’

‘Yes, you are. I can tell. Come home with me. You won’t be disappointed, I promise.’

‘Not before I see a medical certificate that you aren’t full of pox.’

‘Ha! ha!’ she said, still clinging to my arm, bursting into a laugh. ‘A doctor with a sense of humour. I’ve known many like you. Come on home.’

Ever optimistic of solving such riddles, for I am a passionate lover of mysteries, I allowed myself to be guided along by my companion, or rather my unexpected enigma.

I shall omit describing the hovel where she lived; you can find any number of such passages in the work of many old and celebrated French poets. Only – and this is a detail you won’t find in Régnier1 – there were two or three portraits of famous doctors hanging on the wall.

How she pampered me! A blazing fire, mulled wine, cigars; and as she waited on me, the peculiar creature lit up a cigar for herself and said:

‘Make yourself at home, dearie, make yourself perfectly comfortable. Doesn’t it remind you of the hospital and the good old days of your youth. Speaking of which, what was it that turned your hair grey? You weren’t like that not so long ago when you did your internship under L—. You were the one, I seem to remember, who always helped him with the serious operations. Now there’s a man who really enjoys cutting, carving and trimming! You were the one who used to pass him his instruments, threads and sponges. And when the operation was over, he would look at his watch and proudly announce: “Under five minutes, gentlemen.” Oh, I get everywhere. I’m very friendly with all the medical gentlemen.’

A few moments later, still addressing me as if we were old friends, she was back on her hobby-horse again:

‘But you are a doctor, aren’t you, my kitten?’

This meaningless refrain made me leap to my feet. ‘No!’ I shouted in a fury.

‘A surgeon, then?’

‘No! No! Not unless someone pays me to cut off your head!’ And I swore at her.

‘Just a moment,’ she replied. ‘I want to show you something.’

She opened a cupboard and took out a packet of papers, which consisted entirely of a collection of portraits of famous doctors of the day, lithographed by Maurin,2 and which for many a year you used to see displayed on the quai Voltaire.

‘How about this one? Do you recognise him?’

‘Of course. It’s X—. The name is written on the bottom too. But I’ve never met him personally.’

‘I was right! Look, here’s Z—. He was the one who said of X— during a lecture to his students: “The monster! The blackness of his soul is revealed by his face!” And all because they disagreed with each other on some point or another. How they laughed about it at the Medical School at the time! Do you remember? And here’s K—. He was the one who denounced to the authorities the insurgents who were under his care at the hospital. That was during the 1848 uprising. How could so handsome a man possess so little charity? Now here’s W—, the famous English doctor. I cornered him during his visit to Paris. You could mistake him for a girl, couldn’t you?’

And as I picked up the packet tied with string which she had placed on the side table, she said: ‘Wait a moment. Those are the interns and this packet contains the externs.’

And she spread out in the shape of a fan a mass of photographic images showing much younger faces.

‘Next time we see each other, you’ll bring me your portrait, won’t you, dearie?’

‘What makes you think,’ I replied, pursuing my own obsession, ‘that I am a doctor?’

‘Because you are so kind and gentle to women!’

‘Curious logic!’ I said to myself.

‘Oh, I hardly ever make a mistake. I have known so many of them. I like their company so much that I sometimes call on them, even though I am not the least bit ill. There are some who say to me coldly: “You are perfectly well!” But there are others who understand me well enough from the looks I give them.’

‘And when they don’t understand you?’

‘Strewth! As I have disturbed them for nothing, I leave ten francs on the mantelpiece. They are so good, so gentle, those men! I discovered at the Pitié hospital a young intern who was as pretty as an angel and ever so polite. How hard they made him work, the poor lad! His friends told me that he was quite penniless because his family is poor and unable to send him anything. That gave me confidence. After all, though I’m not as still a good-looking woman. I told him to come and see me as often as he liked. You don’t need any money, I said, so no worries on that score. I didn’t tell him this straight out, you understand, but he knew what I meant; the last thing I wanted to do was humiliate him, the dear child. Would you believe it that I have a strange fantasy which I daren’t even mention to him? I would like him to come and see me complete with his instruments and his operating gown spotted with blood!’

She said this in a perfectly candid manner, just as a tender young man might say to the actress with whom he is in love that he wants to see her in the dress she wore when she created some famous part.

I returned obstinately to the subject which fascinated me: ‘Can you remember the first time you had this fantasy and how it came about?’

She didn’t grasp my question at first and it was only with the greatest of difficulty that I made myself understood. When she replied it was with a sad expression and, as far I remember, she even averted her eyes: ‘I don’t know … I can’t remember.’

What strange phenomena we find in a great city, all we need to do is stroll about with our eyes open. Life swarms with innocent monsters. Lord, creator of all things, you, the Master; you who wrote the Holy Law and gave us Liberty; you the sovereign who lets us do as we please, you the judge who forgives us; you who are full of motives and causes, and who perhaps implanted a taste for horror in my mind so as to win over my heart, like a cure at the tip of a knife-blade; Lord, have pity, have pity on madmen and madwomen! Oh, Creator! Can monsters exist in the sight of Him who alone knows how they were invented, how they invented themselves, and how they might not have invented themselves?

1 Régnier. Mathurin Régnier (1573–1613), French poet famous for his satirical portraits.

2 Maurin. Nicolas-Eustache Maurin (1799–1850), French lithographer.

The Penitent

Catulle Mendès

With her veil pulled down to her chin, muffled in furs, and grasping her skirt in both hands like a woman who has dressed in haste, the little baroness darted out into the street where the early morning mist still hovered over the ground. She stopped for a moment in mid step, as if hesitating, and glanced to her right and left with the neck movements of a bird perched on a branch unable to make up its mind in which direction it should fly off. Then, she precipitated herself into a cab, calling out an address to the driver. As soon as she was huddled in a corner, still shivering with cold, or perhaps fear, her muff against her lips, snug amongst the warmth of velvet and silk, a pink and black object slipped to the floor from beneath her coat: a satin corset padded inside the empty cups in order to swell the size of the breasts. What an unimaginable occurrence! The baroness, exquisite woman of the world that she was, looked no different from any other common tart shyly making her way home through the morning streets having neglected to don the fragile armour of whale-bone whose ineffectiveness was clearly proclaimed by the defeats of the previous night. She did not even stoop to pick up the corset. She was reliving every guilty moment of the charming night she had passed in a bachelor’s apartment, where the perfume of the boudoir had been mixed with the smell of Russian leather and fine cigars between walls decorated with ancient coats-of-arms and crossed swords; she dreamt of the sudden transport of an unexpected embrace, of the frenzied unclasping of garments, and of lingering caresses with their languid promise of acceptance and denial. From time to time, she turned her gaze towards the street, which was still grey but gradually becoming pink; under the arches of the main entrances to the buildings dairymen were lining up t

heir pewter churns with copper lids; outside a half-open shop a porter was delivering the morning papers to a woman who was rubbing the sleep from her eyes; office workers flitted along the walls, thin, dark shadows, with their collars turned up and a croissant between their teeth. But she looked without seeing, still recalling the carnal joys of the night, hugging herself in order to prevent their memory from escaping as if they were some garment whose material is soft against the skin.

The cab drove past a church.

The baroness saw the enormous sombre portal which looked as though it is never opened and, to the right, a side door which was ajar. As if struck by some sudden revelation, a strange gleam came into her eyes, all the more remarkable because of the gentleness of their expression, behind her veil – the first glimmer of desire or the sign of a fresh curiosity awakening within her. A laugh – crafty, cruel, slightly mocking, though none the less charming – came to her lips. ‘Coachman! Stop the horses!’ she shouted as she bundled the corset under her coat. She got out of the cab and went into the church, which was deserted except for two or three old women kneeling as they muttered their prayers to themselves by a confessional box, the stout black soles of their shoes plainly visible beneath the muddy hems of their skirts. At that moment a tall, young priest, austere and devout in appearance, emerged from the vestry and made his way towards the tribunal of penitence. The little baroness installed herself on a pew a little to one side and bowed her head while awaiting her turn. She buried her head in her handkerchief. The examination of her conscience was undoubtedly an extremely edifying experience.

***

And why not? Is it not possible to be a good Christian and in love at the same time? Do not the sins of the flesh share the same joys and, alas, the same sense of remorse? We repent our fault with the same ardour with which we commit it; we are as sincere before God as we are with our lover. Mouths which mutter the maddest and most profane promises do so only in order to receive forgiveness; the memory of our transports of delight are but an invocation to the mortification of the flesh. And heaven, whose mercy is infinite, does not fail to welcome the penitent sinner, even when that same sinner has managed to escape from evil in order to purify herself in the well of goodness only a few minutes before – even when her precocious repentance leaves behind it in the temple of God a distinctly sexual odour.

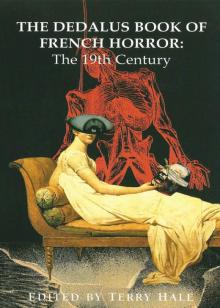

The Dedalus Book of French Horror: The 19th Century

The Dedalus Book of French Horror: The 19th Century