- Home

- Terry Hale

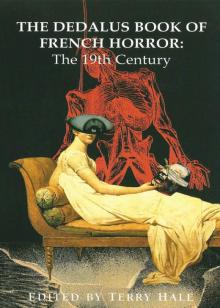

The Dedalus Book of French Horror: The 19th Century Page 6

The Dedalus Book of French Horror: The 19th Century Read online

Page 6

The crew did not blush and weep; no, the crew simply heaved a sigh of relief since Belissan’s latest hare-brained scheme had effectively removed him from their presence.

But as well as rolling around discussing philosophical matters with his calf, Belissan tried to keep his new friend amused by blowing in his eyes and poking pieces of straw up his nostrils. So much so that the calf’s patience began to wear thin until, completely losing his temper, he butted Belissan in the stomach breaking three of his ribs. When they docked at Callao, he was dying. The ship’s company counted on his death; but, as a result of the care shown by the head of the Mission Station at Lima, the damned clerk recovered and at the last minute before the ship set sail for the Spice Islands was fit enough to be carried on board again.

The captain was too upright a man to leave Belissan in Peru, and allowed him back on board with an oath. Realising that he was nearing the end of his voyage, and hoping to shorten it still further, he suggested to Claude that he should disembark at the Marquesas Islands, which were well-known and had been explored by Marchand, and according to the latter were as cytherean as the Society Islands.

The aristocratic name of this cluster of islands slightly disturbed Belissan, but having sailed on La Comtesse de Cérigny, there was no reason why he should not disembark at the Marquesas. He consented readily enough to this change of plan, especially when he was shown on a map that the Marquesas were much closer than Tahiti.

Two months after calling into Acapulco, the brig hove-to downwind of the most easterly of the Marquesas Islands; a heavily-armed rowing-boat deposited Claude Belissan, to the great rejoicing of the crew, at the meridional tip of the island of Hatouhougou just before dawn; then the rowing-boat rejoined the brig which set sail for the south.

IV

How Claude Belissan at last found the Promised Land of social equality and philanthropy

‘At last I set foot in the land of liberty and equality!’ exclaimed Belissan. ‘At last I see the birth place of those sons of nature who have remained men of nature. Here I shall drink water straight from the spring; the fruits of the trees and the occasional shellfish shall sustain me; this sweet-smelling grass shall be my bed; for clothes I shall … No, there is no need for clothes. Was I born wearing clothes? Clothes are nothing more than the product of social injustices. Here, nature reigns; here I shall assume my natural condition. Forget Europe, I no longer care two pins for civilisation; I am out of reach now of France, kings, courtesans and Danish horses!’ And as he shouted these words, he threw his shiny silk britches, his blue ratteen frock-coat and his quilted waist-coat as far away from him as he could.

‘Long live nature!’ he continued. ‘Nature which has no need of the pitiful and ridiculous industry of the so-called civilised world!’

But even as he uttered these words, he was disturbed by the sound of gunfire; then, as the sun had now risen and it was possible to see clearly, he caught his first terrifying sight of Toa-ka-Magarow, sovereign chief, autocrat, emperor and king of the island of Hatouhouhou.

This worthy seigneur was of a commanding stature, tattooed in red and blue, with a long, straight nose, a low forehead, and he had a lower lip which was greatly elongated by the weight of some kind of small bowl made from a coconut shell which was suspended by means of a ring set into his skin. What was more, Toa-ka-Magarow carried an English rifle in his hand and he strutted about proudly in an old military tunic with epaulettes which he had probably bartered or stolen; apart from a tight loin-cloth, he was otherwise naked. I shall only mention in passing, given its distasteful nature, the Cross of Saint-Louis which was held in place by another ring pierced through the nasal cartilage.

As soon as he had fired his rifle, he uttered such a savage and guttural cry that Belissan was transfixed where he stood. But it was for Belissan’s benefit that he had made the sound. Toa-ka-Magarow now uttered a second cry, though this one was cut short: then some kind of laugh or grinding of his teeth caused the small bowl to oscillate and made the Cross of Saint-Louis jiggle from one nostril to the other.

Now that the rifle was no longer aimed at him, Claude Belissan regained his courage and stood his ground.

‘After all,’ he said to himself, ‘we are all equals here; this is my brother. What do I have to fear?’

Claude stepped forward bravely and held out his hand to the great chief.

At this display of friendship and familiarity, which the autocrat of Hatouhouhou had never before experienced, the latter gave vent to a tremendous high-pitched shriek of such anger and wrath that Belissan leapt into the air.

But his surprise gave way to terror when the great chief, by means of an expressive pantomime, pointed out to the clerk his epaulettes, his Cross of Saint-Louis, and some old pieces of copper attached to his legs with string, the implication clearly being that he was the chief, king, master and that Belissan owed him his respect, submission and obedience, which he further demonstrated by half-bending his knees and crossing his arms over his stomach. The lesson concluded with a fearful twirling of the rifle which whizzed around Belissan’s ears, such was the dexterity of the savage in wielding his weapon.

And Belissan fell to his knees bathed in sweat. What a bizarre picture this formed, this athletic savage, with his face painted half in red and half in blue, his gleaming eyes, his swollen lips, his teeth blackened with betel, his gold epaulettes, his crinkly hair, brushed, knotted, pleated and all covered in an orange powder sprinkled with shells of every colour, what an imposing figure he was as he stood there, his head scornfully cocked, taking stock of the naked Belissan, trembling with fear, green with terror, kneeling, arms crossed and eyes fixed before him.

One would need to be a profound psychologist to be able to analyse the tumultuous thoughts flying around Belissan’s head, colliding with each other, locked in mortal combat: the clerk’s former ideas pitted against the incontestable evidence of his situation. And for what felt like an eternity, Belissan reproached himself bitterly, realising that he preferred to be splashed with mud by Danish horses, suffer the sarcasms of the handsome footman, and be the butt of Catherine’s coquetry, rather than to depend on the unpredictable humour of his friend, brother, and equal: the man of nature.

But what irritated him more than anything was not that he had been forced to prostrate himself before a symbol of power but to see that this symbol was enshrined in an old European tunic which reminded him so poignantly of the social distinctions which he had sought to flee.

It is impossible to say to what speculative heights Belissan would have soared had not Toa-ka-Magarow signalled him to rise, reinforcing the order by jabbing him in the kidneys with the butt of his rifle.

The two equals before nature arrived in the village.

And if Belissan still had the force to close his jaw, he would undoubtedly have ground his teeth at the sight of one particular hut, a brightly-painted hut which was built on a slight elevation; in short, a hut clearly distinguishable from the rest as an aristocratic hut, a seigniorial hut, a princely hut, a royal hut.

This was the hut of Toa-ka-Magarow.

And Claude Belissan, still walking in front of the man of nature, climbed down into a sort of little cellar close by the chief’s habitation.

Claude Belissan was held prisoner in this cellar.

For the next week, Claude’s only company was some sort of bamboo cane to which a wicker-basket was attached containing coconuts and the produce of the bread-fruit tree. This bamboo entered and departed by a small window.

During this week, his social and political ideas went through a number of changes. But these changes should remain private, and we shall remain discreet on this point.

At the end of a week, Belissan was dragged from the cellar, bathed, perfumed, tattooed, his nose and ears were squeezed, beads of every colour were placed around his forehead, he was made to lie on a sort of stretcher, and two of Toa-ka-Magarow’s strongest subjects carried him to the top of a mountain where a temple of ree

ds had been built.

‘They intend either to canonise me or play blindman’s bluff,’ thought Belissan, who could no longer see because his eyes were covered with beads, feeling more and more terrified.

When they arrived there, Claude was made to stand up and he was tied to a post.

At the base of the post there was a stone trough.

A multitude of hymns, psalms and prayers were chanted.

And Toa-ka-Magarow, in whom theocratic as well as temporal power was vested, performed some contortions before stepping up to Claude wielding a long knife with a ribbed blade.

The clerk’s blood dripped into the trough.

At this sharp, cold, and painful sensation, Claude, by one of those singular tricks of the memory, thought of his attic room and the summer shower which had alone determined the chain of cause and effect which had led him to the cannibal’s knife; and as a result of a sudden flash of intuition, he understood everything that had happened to him.

And in the grip of some fantastic delirium, he imagined that the Danish horses, the handsome footman and Catherine were all circling him making whooping sounds.

He remembered nothing more.

And this was the fate of Claude Belissan, former clerk to the public prosecutor, man of nature, who served as a feast for the noble savages of Hatouhougou after they had respectfully offered his ears, considered the most delicate part of the human body, to Toa-ka-Magarow.

1 Louis Antoine de Bougainville (1729–1811). French navigator who explored the South Pacific as leader of a French naval force which sailed around the world (1766–1769).

Solange

Alexandre Dumas

Night had completely come upon us during M. Ledru’s narrative. The company in the drawing-room appeared like mute and motionless shadows, so much we feared he might break off; for we perfectly understood that the terrible tale he had just related was but the prologue to another still more terrible.

Not a breath was heard. The doctor alone opened his mouth; I pressed his hand to prevent his speaking; and so, indeed, he kept silent.

After a few seconds, M. Ledru continued:

I had just left the abbey, and was crossing the Place Taranne, on my way to the Rue de Tournon, where I lodged, when I heard a woman’s voice calling for help.

It could not be that she had fallen among thieves or robbers, for it was scarcely ten o’clock at night. I ran to the corner of the square whence the cry had proceeded, and saw, by the light of the moon issuing from behind a cloud, a woman who was struggling to escape from a patrol of sans-culottes.

The woman, on her side, perceived me; and remarking by my attire that I was not altogether a plebeian, she sprang towards me, exclaiming:

‘Stay, here is M. Albert, whom I am acquainted with; he will tell you that I really am the daughter of Mother Ledieu, the laundress.’

At the same time the poor woman, all pale and trembling, seized me by the arm, and clung to me as the shipwrecked sailor clings to the plank he has laid hold of.

‘The daughter of Mother Ledieu! be it so; but you have got no identity card, my fine lady; so you must come along with us to the guard-house.’

The young woman pressed my arm. I felt the terror and entreaty implied by that pressure; I understood her.

As she had called me by the first name that had offered itself to her mind, I called her likewise by the first that occurred to me.

‘What! is it you, my poor Solange?’ said I to her; ‘what has happened to you?’

‘You see, gentlemen,’ she resumed.

‘I think you might say citizens.’

‘Hear me, Mister Sergeant; it is not my fault if I speak as I do,’ said the young girl. ‘My mother had some customers in high life, and was accustomed to be polite; so that I have acquired a bad habit – I am well aware of it – an aristocratic habit. But what’s to be done? I cannot break myself of it.’

There was a degree of raillery in this answer, in spite of her trembling voice, which I alone understood. I wondered who the woman could be. There were no means of solving the problem. Still I was sure she was not the daughter of a laundress.

‘You asked me what has happened to me?’ she continued. ‘Citizen Albert, this is the case. I went to carry home some linen; the mistress of the house was not at home, and I waited till her return to get my money. In these times, you know, every one wants his money. So night came on; I had expected to get back before the close of day; I had not brought my identity card with me; I fell into the hands of these gentlemen – excuse me, I mean these citizens; they asked me for my card; I told them I had none, and they were going to drag me to the guard-house. Thereupon I cried out, you ran up, and as you proved to be an acquaintance, I felt re-assured. I said to myself: “Since M. Albert knows my name is Solange, and that I am the daughter of Mother Ledieu, he will answer for me;” will you not, Monsieur Albert?’

‘Certainly I will answer for you.’

‘Good!’ said the head of the patrol; ‘and who will answer for thee, young fop?’

‘Danton! Will that suit thee? Is he a good patriot?’

‘Oh! if Danton answers for thee, there is no more to be said.’

‘Well! this is one of the meeting days at the Cordelier Club;1 let us go thither.’

‘Let us go thither,’ said the sergeant. ‘Citizens of the sansculottes, forward, march!’

The Cordelier Club met in the old convent of the Cordeliers, in the Rue de l’Observance; we soon reached the place. On our arrival, I tore a page out of my pocket-book, wrote a few words in pencil, and requested the sergeant to carry the note to Danton, whilst we were left with the corporal and the patrol.

The sergeant went into the club, and returned with Danton.

‘What!’ said he to me, ‘have they arrested thee, my friend; thee, the friend of Camille,2 and one of the best republicans that exist? How very odd! Citizen Sergeant,’ added he, turning towards the leader of the band, ‘I will answer for him. Will that do?’

‘Thou answerest for him! but dost thou answer for her?’ rejoined the obstinate sergeant.

‘Her! Of whom dost thou speak?’

‘Of this woman, to be sure!’

‘Of him, or her, and all that are along with him; art thou satisfied?’

‘Yes, I am satisfied,’ said the sergeant, ‘especially to have seen thee.’

‘Look at me at thy leisure, whilst thou hast me.’

‘Thanks! – continue to support, as thou dost, the people’s interests, and be sure the people will be grateful to thee.’

‘Oh, yes! I fully rely upon it!’ said Danton.

‘Wilt thou give me thy hand to shake?’ continued the sergeant.

‘Why shouldn’t I?’

And Danton gave him his hand.

‘Long live Danton!’ cried the sergeant.

‘Long live Danton!’ repeated the patrol.

The sans-culottes moved off with their leader, who, before he had gone many yards, faced about, and, flourishing his red cap, cried out again: ‘Long live Danton!’ the cry being repeated by his men.

I was going to thank Danton, when his name was called out several times within the hall. ‘Danton! Danton!’ shouted many voices. ‘Danton, to the tribunal!’

‘Excuse me, my dear fellow,’ said he; ‘you hear them, – shake hands, and allow me to return. Stay! I gave my right to the sergeant – take my left; who knows – the worthy patriot may have had the itch.’3

Then turning round:

‘Here I am!’ said he, in that powerful voice which excited and appeased the storms of the street; ‘here I am, wait a moment.’

Then he rushed back into the club.

I remained alone with the fair stranger.

‘Now, madame,’ said I to her, ‘where must I take you? I am at your command.’

‘Why, to Mother Ledieu’s!’ answered she, laughing; ‘you know she is my mother.’

‘But where lives this Mother Ledieu?’

‘Ru

e Ferou, No. 24.’

‘Let us go to Mother Ledieu, then.’

We descended the street, went through several others, crossed the Place Saint Sulpice, and came at length to the Rue Ferou.

We neither of us had spoken a word the whole way; but, as the moon was shining splendidly, I had full time to examine her.

She was a lovely girl of two-and-twenty, a brunette, with large open blue eyes, beaming with expression, a fine straight nose, an arch mouth, teeth as white as pearls, hands fit for a princess, and small feet. All these attractions, under the homely garb of Mother Ledieu’s daughter, had preserved an aristocratic look which had, fairly enough, roused the suspicions of the worthy sergeant.

On reaching the house, we stood still a moment looking at each other.

‘Well, what is your pleasure now, my dear Monsieur Albert?’ inquired the stranger, smiling.

‘I wanted to say, my dear Solange, that there was little use in our meeting, if we are to part so hastily.’

‘Many pardons, sir. I think it has been of much use, though; for, had I not met you, I should have been taken to the guard-house; they would have found out that I was not the daughter of Mother Ledieu; I should have been discovered to be an aristocrat, and they might have cut my head off.’

‘So, then, you confess that you are an aristocrat?’

‘I confess nothing.’

‘Come, tell me your name, at least.’

‘Solange.’

‘I gave you that name at random; it is not yours.’

‘Never mind; I like it, and shall keep it – for you, at least.’

‘Why need you keep it for me, if I am not to see you again?’

‘I don’t say that. All I say is, that if we meet again, you need not know my name, nor I yours. I gave you the name of Albert; keep that name, as I shall keep that of Solange.’

The Dedalus Book of French Horror: The 19th Century

The Dedalus Book of French Horror: The 19th Century