- Home

- Terry Hale

The Dedalus Book of French Horror: The 19th Century Page 8

The Dedalus Book of French Horror: The 19th Century Read online

Page 8

About five o’clock the dreadful train arrived. The bodies were cast pell-mell into the tumbrel, the heads pell-mell into the sack.

I used to take out at random one or two heads and one or two bodies; the remainder were thrown into one common grave.

The next day the heads and bodies on which I had tried my experiments the day before were added to the new heap of sufferers. My brother used to assist me almost always in these examinations.

Amidst all this contact with death, my love for Solange increased every day. On her side, the poor child loved me with her whole heart.

Often and often I had thought of making her my wife. We had frequently surveyed in our fancy the joy of such a union; but, in order to become my wife, Solange must have told her name; and her name – being that of an emigrant, of an aristocrat, of an outlaw – would have been fatal to her.

Her father had written to her several times to hasten her departure; but she had told him our love. She had asked his consent to our marriage, and he had granted it. On that side, therefore, all went well.

Meanwhile, amidst all these terrific trials, one still more terrific than the rest had deeply afflicted us both.

It was the trial of the queen, Marie-Antoinette.

Begun on the 4th of October, 1793, this trial had been actively proceeded with. On the 14th of October she had appeared before the revolutionary tribunal; on the 16th, at four in the morning, the ill-fated widow had been condemned; and the same day, at eleven, she was beheaded on the scaffold.

In the morning I had received a letter from Solange, who wrote to say she would not let such a day pass without seeing me.

I arrived about two o’clock at our little apartment in the Rue Taranne, where I found Solange in tears. I was myself most sensibly affected by this execution. The queen had been very kind to me in my youth, and I had never forgotten that indulgence.

I shall ever remember that day; it fell on a Thursday. There was something heavier than sorrow over Paris; there was affright.

As for me, I experienced a strange dejection – something like the presentiment of a great misfortune. I had wished to console Solange, who lay upon my bosom weeping; but no words of comfort could I command, because my own heart was inconsolable.

We passed the night together as usual; it was still sadder than the day had been. I recollect there was a dog locked up in the room over our heads, who kept howling until two in the morning.

Next day we made inquiries. His master had gone out and taken the key; he had been arrested in the street, taken before the bloody tribunal, condemned at three o’clock, and executed at four.

We were forced to separate. Solange’s classes began at nine in the morning. Her boarding-school was situated near the Garden of Plants. I hesitated a long time before I would let her go. She was equally unwilling to leave me; but to stop out for two days together would have exposed her to an investigation, which in her circumstances would have been dangerous.

I ordered a coach, and went with her to the corner of the Rue des Fosses-Saint-Bernard; where I got out. During the whole drive, we had held each other firmly embraced without uttering a word, mingling our tears together, which flowed over our lips, our sweet kisses being embittered by them.

I alighted from the coach; but, instead of going my way, I stood fixed to the spot, looking after the carriage which bore her away. When the coach had gone about twenty yards, it stopped, Solange looked out of the door, as though she had guessed I was still there. I ran up. I got into the vehicle once more; and put up the windows. Again I hugged her in my arms. But nine o’clock struck by the parish church. I wiped the tears from her eyes, closed her mouth with kiss upon kiss, and, springing out of the coach, hastened away running.

I thought that Solange called me back; but these tears, these faltering delays, might be remarked. I had the mournful courage not to return.

I returned home in despair; I spent the whole day in writing to Solange; in the evening I sent her a book.

I had just left my letter at the post-office, when I received one from her.

She had been very much scolded; they had worried her with a host of questions, and threatened to deprive her of her next holiday.

Her next holiday was the following Sunday; but Solange promised me that whatever might come, even though she broke with the schoolmistress, she would see me on that day.

I, too, made the same vow; it seemed to me that if I were to be seven days without seeing her, which would happen if she lost her first holiday, I should go mad.

The more so that Solange expressed some uneasiness, as a letter she had found at the boarding-school on her return, and which was from her father, appeared to her to have been unsealed.

I spent a bad night, and a still worse day on the morrow. I wrote as usual to Solange; and, as it was the day of my experiments, I called upon my brother about three o’clock to take him with me to Clamart.

My brother was not at home; I went off by myself.

The weather was awful; the sky was dissolving into rain – that cold heavy rain which foretells the winter. All the way along, I heard the street-criers howling in a croaking voice the list of the convicts of the day; it was numerous; it contained men, women, and children. The bloody harvest was a plentiful one, and there would be subjects enough for that evening’s experiments.

The days were growing short. When I reached Clamart, at four o’clock, it was almost dark.

The look of that cemetery, with its large tombs recendy closed, its few trees clacking to the wind like skeletons, was gloomy and almost hideous.

Wherever the mould had been turned over, you saw nothing but grass, thistles, or nettles. And each succeeding day the fresh mould was thrown over the dark grass.

In the midst of all these swellings in the ground, the pit for the day was agape, expecting its prey. They had foreseen the surplus of convicts, and so the pit was larger and deeper than usual.

I drew near to it undesignedly. The bottom was full of water. Poor, cold, naked corpses they were going to throw into that water, as cold as themselves!

On reaching the orifice of the grave, my foot slipped, and I was on the point of falling in; my hair stood up with horror. I was wet, and felt a chill. I went away towards the laboratory.

It was, as I have said, an old chapel; I looked round. What made me look? That I don’t know. I looked on the walls, and on what had once been the altar, for some sign of worship; the wall was bare, the altar was stripped. There, where formerly had stood the tabernacle – that is to say, God and life – was now a fleshless skull without hair: that is to say, death and vacancy.

I lighted my candle, and set it down on the table of operation, covered over with several tools of singular shape, that I had myself invented. I sat down – thinking of what? Of that poor queen, whom I had seen so beautiful, so happy, and so adored; who but yesterday, smitten with the imprecations of a whole people, had been drawn in a cart to the scaffold, and who, at that moment, with head sundered from the body, slept in the coffin of the poor; she who had once slept beneath the gilded canopies of the Tuileries, Versailles, and Saint-Cloud.

Every one knows, in our time, that the coffin in which the widow of Louis XVI was enclosed cost but seven francs!

Whilst I was sunk in these gloomy reflections, the rain increased, the wind squalled aloud, sweeping its plaintive dole among the branches of the trees, among the blades of grass.

This noise was soon intermingled with another like murmuring thunder; only this thunder, instead of roaring in the sky, was leaping over the ground, and shaking it as it came on.

It was the wheels of the red tumbrel returning from the Place de la Revolution and entering Clamart.

The door of the little chapel was opened, and two men, dripping with water, came in, carrying a sack.

One of these was that very Legros, whom I had visited in prison, the other a grave-digger.

‘See, Monsieur Ledru,’ said the executioner’s assistant to me

, ‘here’s what you want; you need not hurry yourself this evening; we are going to leave you the whole batch; they shall be buried tomorrow; it will be light then, they won’t take cold by spending a night in the open air.’

Whereupon, with a ghastly laugh, the two hirelings of death set the sack down in the corner near the old altar opposite me on my left.

After which they went away without shutting the door, which began to beat against its cage, letting in the wind, which made the flame of the candle waver about its long black wick.

I heard them take out the horse, shut the door of the burial-ground, and depart, leaving the tumbrel full of dead trunks.

I felt a longing desire to go with them, but I do not know how it was something held me in my chair – all in a tremor. Certainly it was not fear, but the noise of that howling wind, of that pelting rain, the squealing of those trees, the hissing gusts of air that made my candle waver, all these together shed an indefinite alarm over my mind, and spread through my frame.

Suddenly methought that a mild and sorrowful voice, a voice proceeding from the very bosom of the little chapel, uttered my name.

‘Albert!’

Oh, what a start I gave! Albert! There was but one person in the world who called me by that name.

With bewildering eyes I looked stealthily round the chapel, which, small as it was, my candle lighted but imperfectly, and then rested them on the sack in the corner, its bloody crimpled canvas distinctly indicating its mournful contents.

Just as my eyes settled on the sack, the same voice, but weaker and still more plaintive, repeated the same name.

‘Albert!’

Freezing with dismay I started to my feet. The voice seemed to proceed from the inside of the sack.

I felt myself to see whether I was asleep or awake. Then stiff and stark, and all my body like a mass of stone, with arms outstretched, I went up to the sack, and put in my hand.

Then I felt as if a pair of lips, still tepid and warm, pressed upon my hand.

I had reached that degree of terror when its very excess restores our courage to us. I took the head up, and returning to my chair, into which I sank, I set it on the table.

Oh, the terrific shriek I gave! That head, whose lips were still warm, whose eyes were still but half closed, was the head of my Solange!

I thought I was mad. Three times I cried aloud:

‘Solange! Solange! Solange!’

At the third cry the eyes opened again, looked at me, let fall two tears, and with a humid gleam, as if the soul was escaping, closed again to open no more.

I arose mad – distracted – raving. I wanted to fly from the place, but the skirt of my coat caught hold of the table; the table fell down, extinguishing the candle, the head rolled along the floor, and I was dragged down in bewilderment.

Then it seemed to me, as I lay on the floor, that I saw the head slide over towards mine; its lips touched my lips, an icy shudder came through my whole frame; I groaned, and fell into a swoon.

The next day, at six in the morning, the grave-diggers found me where I lay, as cold as the stone beneath me.

Solange, discovered by the letter from her father, had been arrested, condemned, and executed in one day.

That head which had spoken to me, those eyes which had looked at me, those lips, which had touched mine, were the lips, eyes, and head of my Solange.

‘You remember, Lenoir,’ continued M. Ledru, turning towards the Chevalier, ‘that was the time I was not expected to recover.’

1 The Cordelier Club was one of the most important political clubs of the left bank during the French Revolution and the power-base of Georges Jacques Danton (1759–1794) – a man whom Dumas, along with many other French Romantic writers, delighted to portray under the dramatic shadow of death.

2 Camille. i.e. Camille Desmoulins (1760–1794), radical journalist active in the Cordelier section and the faction that gathered round Danton in the Assembly.

3 The ‘itch’ is, presumably, scrofula. The original translator for The London Journal added the following footnote – worth repeating as it clearly demonstrates the sensitivities of the nineteenth-century British audience who saw in such fictions a reflection of their own social and political situation: ‘This sneer at the poor is very disgraceful. It is likewise libellous. Man for man, the poor are ten times healthier than the rich; and the itch is a disease which the poor man never has unless he is under-fed, and consequently plundered – like the poor children of Tooting.’

4 General Marceau. One of two generals dispatched by the Convention in September 1793 to suppress the Vendean uprising.

Monsieur de l’Argentière, Public Prosecutor

Pétrus Borel

I

A single candle placed on a small table alone shed light upon the vast airy chamber. But for the clatter of glasses and silverware, and the occasional burst of voices, it could easily have been mistaken for the lamp which burns at a funeral wake. Peering with deliberation through this chiaroscuro, just as one examines a Rembrandt etching, it was possible to make out a dining room decorated in the style of Louis XV, which the classicists of the absurdo-Roman school maliciously call the Rococo. And, appropriately enough, both the stringcourse and the necking of the cornice running around the ceiling were indeed sinewy and well-delineated, totally unlike those of the entablature of the Erechtheum, the temple of Antoninus and Faustine, or the Arch of Drusus. In compensation, there was an utter dearth of overhanging projections, dripstones, watercourses and outer fillets, designed to channel and repulse the rains which never fell. Nor were the archways surmounted by coping-stones of the kind called Attic, designed to channel and repulse the rains which likewise never fell. It would also be true to say that the height of the archways was not two-and-a-half times their width. Finally, no attention whatsoever had been paid to the illustrissimo signor Jacopo Barrozio da Vignola and the rule of the five orders had been completely disregarded.1

Still, it could not be claimed that this interior was merely a worthless pastiche of the clumsy architecture of Paestum; of the cold, bare, rigid, repetitive architecture of Athens; or of the derivative and bastardised architecture of Rome. This was a building which had its own physiognomy, shape, and particular charm. The perfect incarnation of its own epoch, each was ideally suited to the other. Indeed, so unique was its physiognomy that, even after the toll taken by the centuries, Louis XIV and Louis XV rococo is still immediately recognisable, a distinction altogether lacking in the work of contemporary craftsmen who provide us with nothing more than illiterate copies of the old styles without imparting any of the character of their own period – so much so that posterity will view the results as no more than second-rate antiques imported from abroad.

The wall-panelling was covered in still-life paintings worthy, though unsigned, of Venninx2 and the mouldings represented pastorals like those which serve as backdrops at the opera, charming scenes of shepherdesses and their swains in the manner of the immortal Watteau. These graceful and delicate pictures, with their bright, pleasing colours, were truly in the style of that great master – an artist whom an ungrateful and unappreciative France should reclaim and hail as one of her principal glories. Let us honour Watteau and Lancret, Carle Vanloo and Lenôtre! Let us honour Hyacinthe Rigault, Boucher, Edelinck, Oudry!3

If truth be told, I believe that I feel equally at home and free to let my imagination wander in these vast seventeenth and eighteenth-century residences as in a Byzantine chapter-house or a Roman cloister. All that reminds us of our fathers and forefathers, buried in a plot of honest French earth, overwhelms my heart with a religious melancholy. Shame on those who remain unmoved, whose pace fails to quicken, on entering one of these old habitations, a manor-house falling to wrack and ruin or a desecrated church!

At the table on which the candle was placed two men were sitting.

The younger of the two remained motionless, his pale head bowed beneath a stream of red hair; his eyes hollow and treacherous,

his nose long and pointed. To say that his whiskers were trimmed squarely on his cheeks like gaiterstraps will disclose that this scene takes place under the Empire, around 1810.

The older one was stocky, the prototype of the native of the plains of Franche-Comté. His thick hair hung heavily, like Babylon’s garden, across his broad, flat face – the face of a nocturnal bird.

The two men were greedily hunched over the table, like two wolves disputing a carcass, but their muttered speech in the echoing hall resembled more the grunting of pigs.

One was less than a wolf: he was a public prosecutor. The other was more than a pig: he was a chief commissioner of police.

The police commissioner had just been appointed to a city in the provinces and was leaving the next day.

The prosecutor had held his office for many years at the Court of Assizes in Paris and was hosting a farewell dinner to celebrate his friend’s promotion.

Both were dressed in black, like doctors in mourning for the murders they had committed.

As they both talked in low voices, and often with full mouths, the negro who tended on them from the doorway – for young prosecutor de l’Argentière treated his staff like coolies and liked to play the indignant aristocrat – could only catch the odd word here and there of their conversation.

‘My dear Bertholin, I enjoyed a truly succulent repast yesterday at our friend Arnauld de Royaumont’s! From his apartments, which give on to the Place de la Grève, I could observe the execution of the seven conspirators that he tried a few days ago. It was absolutely exquisite! Every time I raised my fork to my mouth, a head fell!’

‘Silly fools! How can they go on believing in their country! They all see themselves as reincarnations of Brutus or Hampden!’4

‘Do you know, they had the effrontery to try and harangue the crowd from the top of the scaffold! They were soon cut off – just like their heads! But not before they could shout out at the top of their lungs: “Long live France! Death to the tyrant! Death to the tyrant!” Stupid oafs! There can be no half-measures with curs like that. Off to the scaffold with them! We mustn’t allow such vermin to deprive the Emperor of his beauty sleep.’

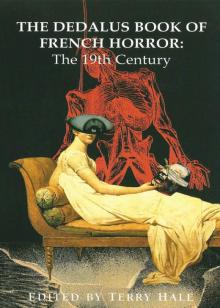

The Dedalus Book of French Horror: The 19th Century

The Dedalus Book of French Horror: The 19th Century