- Home

- Terry Hale

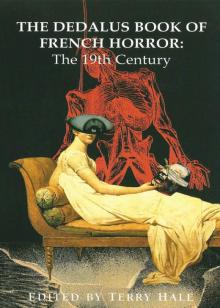

The Dedalus Book of French Horror: The 19th Century Page 9

The Dedalus Book of French Horror: The 19th Century Read online

Page 9

Judging by these scraps of conversation, it was an extremely edifying discussion, and it was greatly to the detriment of the legal profession that the wretched negro could not benefit more fully from it.

By the time dessert was served, the Corsican wine had raised the decibels a fraction and the talk became noisy and ribald such that it would have been easy to note down the following:

‘By the way, my dear de l’Argentière, given that you are so experienced in subterfuge and chicanery, perhaps you could give me some advice. It is absolutely essential that I depart tomorrow morning, yet I have arranged an extremely appetising rendezvous for tomorrow evening.’

‘Very simple. Either I shall leave town in your place so that you are free to go to your rendezvous, or you shall depart tomorrow and I will go in your place.’

‘But seriously?’

‘You will have to provide me with more details if you want me to give you a considered opinion. Is your rendezvous with a man or a woman? Is it business or pleasure?’

‘A woman … and pleasure is not out of the question.’

‘In the name of Père Duchêne!5 If you forget for a moment the Aristotelian rule concerning unity of place, the solution to your problem is easy. Tell the princess that you have changed the rendezvous point to Auxerre and have her follow you there.’

‘And if the little vixen turns out to be another Lucretia?’6

‘By the gods, I’d play the little Jupiter: one way or another I’d force the beautiful Europa to pack her bags and come after me.’

‘And the next day?’

‘What next day? I’d leave her stranded at Auxerre still thinking of me!’

‘And what do you think the poor creature would do next?’

‘Poor creature? She’d have me to thank for turning her into a one-woman cottage industry! The only thing left for her to do would be to hop on a coach home and start looking for a good wet-nurse!’

‘What an unmitigated rake you are, de l’Argentière! No, no, she does not merit such harsh treatment, she’s no more than a child!’

‘What a sentimental ass you can be! Quick, handkerchiefs!’

‘No, she is the girl of my dreams, a little wood-nymph whose beauty enchants me …’

‘Lures you to the edge of the precipice, more likely.’

‘I would run after her … Even you could not help falling in love with her should you ever clap eyes on her.’

‘A plague on all you bashful lovers!’

‘She would melt even your iron heart.’

‘You old bear! In what cemetery did you unearth such fair flesh? And how the devil did you win the favours of this walking marvel?’

‘As for her favours, I never boasted that I had won them. Some matters one should not lie about. And as for unearthing her, that was more by chance than good management. We live in the same house and I have known her ever since she was a little girl. She was always elegantly dressed and she used to curtsy graciously before me every time our paths crossed. How the very sight of her used to sadden me, for I was celibate and lonely then! How I envied her father, blessed with such a beautiful child; though there always seemed to me, then as now, something slightly ridiculous about fatherhood. The father – this was at the time of the Consulate – had some high ranking position which kept the family’s coffers well filled; until, that is, he got mixed up in some trumped up conspiracy or other. Anyway, one fine morning, the Emperor’s men came to arrest him and he’s been locked away like a political prisoner from that day to this, though there never was a trial. His Majesty the Emperor is good at harbouring a grudge. The family have been in straightened circumstances ever since. Apolline grew poorer and more beautiful every year until she finally reached the age at which coquetry and the taste for finery made her acutely aware that she had not much more than a few expensive rags to her name, though she never lost that imperial air of hers. How sad it is to see a beautiful girl ashamed to go abroad in daylight! Her entire wardrobe consisted of a torn cashmere and a pair of worn out shoes, and in these she was obliged to go and buy cheap vegetables at the local market. How my heart used to bleed for her! What could be more poignant or more galling?

‘Stop laughing, de l’Argentière! If you want to laugh, laugh at me, not at her! Have you no feelings whatsoever?’

‘What I find so amusing, Bertholin, is to hear such fine sentiments coming from your lips. I am unused to it. You, a confirmed bachelor and inveterate misogynist! Is there something wrong with you? It’s hardly a propitious moment to start playing the devoted lover. You’d better get used to the part of Father Cassandre,7 you’ve missed the boat as Harlequin.’

‘Was that intended as an insult?’

‘Funnier and funnier! It must be love!’

‘Very well! Yes, I am in love! I have every reason to be in love and there’s no reason for me to feel ashamed of a love born of pity. I bless God …’

‘You’ll do nothing of the sort!’

‘I bless God that I have never committed myself until now so that I may act as this poor orphan’s guardian.’

‘You have been reading too much Chateaubriand, is that it?’

‘I tell you, I have every intention of being the guardian angel of this abandoned child, whom need would otherwise drive to death or prostitution. She has absolutely no-one to turn to: her poor mother, undermined by years of privations, and weakened further still by her daughter’s sufferings, died three months ago. When Apolline’s cries informed me that her mother had passed away, I immediately went up to comfort her and offer her my protection. I arranged the funeral, and got the town hall to pay for the burial. This was the first time I had spoken to Apolline. I cannot describe to you the effect it had on me as I went into that bare room, when she kissed my hand and, with a voice choked with tears, thanked me for my help. I was beside myself. All I can remember was that I burst into tears as well. Overwhelmed, she knelt down by her mother’s rickety bed and prayed for God to restore her to life.

‘That hour took ten years off my life!

‘And our love grew out of this compassion.

‘I called on her a few days later. All the time we were talking, I could not help but notice her embarrassment. She never moved from where she was seated, her hands folded on her lap. When she stood up to show me to the door, I saw that the front of her dress was torn and ragged, and that she had tried to hide her poverty with her hands.

‘I became increasingly enamoured of her manner, which was both sweet and sad, not to say besotted by her rare beauty. After courting her assiduously for some time, I declared my passion for her. She replied that she had too high a regard for me to presume that I wished to take advantage of her destitution, that she had complete faith in my integrity and the sincerity of my feelings, but that she had resolved to take leave of a world in which she had already suffered too greatly. Accordingly, she had written to the superior of the convent of Saint-Thomas and asked to be admitted as a novice. It was no easy matter to dissuade her from this plan, but I finally managed to convince her that the austerity of the convent, after all the hardships she had suffered, would surely kill her.

‘I do not delude myself that Apolline loves me as much as I do her. She admires me as a father. She sees me more as a benevolent teacher or a sympathetic friend. She is attracted to me in part because until now she has only encountered those who are selfish and ferocious. She is good, sensitive and wise, entirely sensible, what more could I ask for? She has declined every present I have brought her: she cannot do otherwise, she says, her honour demands it. Decent girls will only accept presents from their husbands. I have promised her that we shall be married shortly, and this thought fills her with joy. It was for that reason – so that we may discuss preparations for the marriage, though who knows what else might happen – that I have made an appointment with her for tomorrow night. I’m not lying about it, here is her letter.’

My Dear Bertholin,

I can only presume that it is

because you are so busy that you have chosen such a late hour to visit me. But I shall obey your wishes, my dearest husband. I shall extinguish my lamp so as not to give rise to any gossip from evil-minded neighbours. Come stealthily.

Your devoted bride.

‘I have decided to depart without telling her anything in order to spare her a painful farewell. If I see her, I suspect that I shall not have the heart to go. I shall write on arrival and, once I am established in my new position, I shall come back and marry her clandestinely. We shall then settle in Auxerre, where I shall tell my associates that we have been married for some time in order to avert suspicions.

‘But come tomorrow depart I must. First, though, I must send some money so that the poor girl doesn’t die of starvation while I am away.

‘Good Lord! Eleven o’clock already! I must be on my way, de l’Argentière!’

On these words, Bertholin rose and went to the door. The public prosecutor, who had listened to his friend’s story attentively, though his face had remained cold and impassive, accompanied him to the bottom of the stairs, still asking questions.

‘I believe you mentioned that Apolline is very beautiful?’

‘Indeed, she is, my friend. I have known many women, but I have never met one as beautiful as this. Picture to yourself Bertin’s Eucharis, Parny’s Eléonore, a nymph, Egeria and Diana all rolled into one! She is tall, gracious and slender; she is as pale and melancholic as an invalid; her hair, which she wears in coils, makes her look even more virginal; her eyebrows are jet black and she has large, languorous, blue eyes.’

‘And she lives at the same address as you?’

‘The same, at the end of the corridor above mine.’

De l’Argentière gripped Bertholin as if he were a dish of food. A strange gesture on his part, he who was usually so cold and disdainful.

II

Nine o’clock was tolling from the Carmelites, the Luxembourg, Saint-Sulpice, the Abbaye-au-Bois, and Saint-Germain-des-Prés as if to serenade the falling night with a frightful din.

At that moment, in the rue Cassette, a man slipped into a house of noble appearance and stole up the stairs like a wolf. He turned into a dark corridor at the top and came to a halt. Through the panels of a door a voice could be heard. He put his ear against the keyhole. A gentle voice was reciting a good-night prayer. He tapped lightly with his finger.

‘Who is it?’

‘Quick, Apolline, it’s me!’

‘Who?’

‘Bertholin!’

Immediately, she half-opened the accursed door which creaked worse than an old pair of shoes, its hinges groaning like a weathervane.

‘Bertholin! My darling!’

‘Apolline! You look adorable!’

‘Forgive me for receiving you so inadequately, without even a light. But my window has no curtains, and you can see straight in from across the street. But what brings you here so late?’

‘My mind has been distracted with business all day; besides that the sunshine is little given to effusions of love. What is love without the night? What is love without its mystery?’

‘I cannot hold you to blame for that, for I myself never feel closer to God than at night, in a dark church. Was that a cough?’

‘Yes. While cooling my heels waiting for the minister, I picked up a cold and a sore throat. I am quite exhausted.’

‘Then that is why your voice sounds so strange and hoarse. But let us talk seriously. Why put off our marriage any longer? If people see us together, I will get a bad reputation.’

‘Have patience, my love. Today I received official confirmation on my posting to the prefecture of Mont-Blanc and I must leave tomorrow. I promise you that as soon as I have settled in and everything is running smoothly, I shall return to celebrate our engagement publicly. We shall leave Paris at once and I will introduce you to my new colleagues as my wife of long standing.’

‘My love, how happy you make me. But you won’t be away long, will you? Alone here, my hopes will be too much for me to bear.’

‘Don’t quibble! If you only knew how much I love you!’

‘But, Bertholin, what are you thinking of? … How dare you kiss me like that!’

‘Darling!’

‘You seem to be intent on using me in a singularly ungentlemanly fashion tonight!’

‘Not at all. I am treating you as a man should treat his wife.’

‘Wife! Am I that already?’

‘When two beings who love each other have made a promise, it does not require the approval of the town hall to render it sacred. The law can only ratify it. We have sworn to love each other for ever, this makes us man and wife. And if we are man and wife why should we not …’

‘Because without God’s blessing it is a sin.’

‘God, like the law, only ratifies.’

‘I cannot fight with you. I am not skilled in debate. I do not deny my weakness. But treat me with generosity.’

‘But I am!’

‘Let go of me, Bertholin! You are unworthy of yourself tonight! What do you want of me? … Monster! How can you abuse me like this? I shall scream!’

‘Do so.’

‘I shall stamp on the floor and the servants will come up.’

‘Oh, Bertholin! You shouldn’t have done that. It was wrong.’

..........................................................................................................................

‘And now you will despise me, you will drive me away and have nothing more to do with a woman so lacking in her duty as to have lost her virtue.’

‘Don’t be silly, Apolline. Have you such a low opinion of my honour. Me, hurt you? Never! The very thought sticks in my throat.’

‘You still love me?’

‘For ever!’

‘But your voice suddenly sounds so different. Heavens, is it really you, Bertholin? What a fool I am! What a strange foreboding I have! What if I have been deceived? It really is you, isn’t it, Bertholin? Answer me!

‘Let me touch your face. Bertholin does not have a beard. Oh, what if I have been deceived!’

‘Young lady,’ said the enigmatic figure in a clear voice, ‘the moral of all this is that one should never receive one’s lovers in the dark.’

At the sound of this strange voice, Apolline fell to the floor in a faint.

When she regained consciousness, she dragged herself noiselessly across the floor to the window where a ray of moonlight shone into the room falling across the head of a man soundly asleep in the armchair. Apolline, trembling, examined his features: he was dressed in black; his head, which rested on his chest, was pale and covered in long flowing red hair; his eyes were cavernous, his nose long and pointed, his cheeks bedecked with red whiskers trimmed squarely like a gaiterstrap passing beneath his chin.

‘Who is this man?’ the unhappy girl asked herself. ‘Oh, base Bertholin. You are behind this infamy! Who would believe it! How terrible to have been taken in like this.’

In the breast pocket of the unknown man she could feel a wallet. She would have given anything to be able to remove it in the hope of discovering the identity of her seducer. But this was impossible as his coat was tightly buttoned.

Confronted by so much mortal anguish, she cursed Bertholin and God.

At last, overwhelmed with grief and tiredness, she crouched down on the floor again which was drenched with her tears.

When she awoke, it was broad daylight. The armchair was empty, and she was alone, face to face with her shame.

III

In the course of the next day the porter went up to Apolline’s room to deliver a purse of money. It was the money that Bertholin had thought to leave anonymously for her after his departure, for he feared that before his return the poor girl, entirely lacking in resources, would be sorely in need.

‘Who is this from?’

‘I don’t know, miss. A stranger asked me to give it to you, without saying another word.’

; ‘Take this money back!’

‘I cannot. His instructions were quite clear: for Miss Apolline.’

‘Take it back, I tell you.’

The poor man was completely dumbfounded.

Apolline, proud and haughty, dismissed him all the more harshly since in her heart she presumed that the purse represented the price of her virtue and that the man in the night was offering her money in order to humiliate and debase her still further.

But the porter, excusing himself, tossed the purse on the table and turned on his heel.

Throughout the rest of the day Apolline was on tenterhooks. Although she could hear nothing, she listened out for any sounds coming from the apartment of Bertholin below, that of footsteps, a piece of furniture being moved, the opening of a door or a window. In vain. She spied in this manner for several days in a row without any more success. At last, one evening she dared to go down and knock; but there was no answer. Bertholin had taken his servants with him.

The imbroglio intensified, and poor Apolline lost her head. Has he moved out? she wondered. Surely I would have heard something. Had he left Paris after plotting this dastardly crime with one of his associates? But no, that was impossible. How could he be capable of such duplicity, such wickedness? No, Bertholin was a sensitive and honest man. Then what is the explanation for all this? In her confusion, she even began to doubt herself, and wonder whether she had not been mistaken in the dark, and that the man her over-wrought imagination had taken for a stranger was none other than Bertholin. But their features were so different. She couldn’t have been dreaming. Nor did the stranger sound like Bertholin or possess his manners. No, it surely wasn’t Bertholin.

About a week after her misadventure, Apolline received a letter from Mont-Blanc. It was from Bertholin, and ran as follows:

My Darling Bride,

The Dedalus Book of French Horror: The 19th Century

The Dedalus Book of French Horror: The 19th Century